Conservation of Mental Energy

Even though we do not have practical means to quantify or measure directly, mental energy is a very useful concept when addressing our insidious addiction to endless thoughts and tendency to drown in the mindstream discussed in the preceding pages. Instead of being fully present here & now, we tend to keep the mind busy elsewhere with distracting thoughts and unhealthy ruminations that sap and drain our vitality. Living habitually not here & now is the definition of a stressful lifestyle, in which our mental energy is chronically depleted by the disconnect between the mind and actions.

The first principle of conservation we need to understand is that we have a finite amount of mental energy allocated to each day and need to use it wisely for things that matter throughout the day without squandering. While the diagram below is an oversimplified model, it illustrates how quickly we can reach a state of mental exhaustion and induce clinical depression if we are not paying close attention to the expenditure of mental energy.

Let us assume that a person wakes up on one Monday morning with 100 units or $100 worth of mental energy. Ideally, the person should go through the entire day without overspending by carefully doling it out as necessary. However, life tends to throw a curve ball and they might end up spending 120 units or $120 worth of mental energy ($20 deficit) on the first day of the week. The next morning (Tuesday), the same person wakes up and goes to work thinking that they had a restful night and forgetting that they have only 80 units of mental energy for the day because they overspent 20 units yesterday and essentially borrowed $20 from today. Imagine the person has another challenging day and ends up spending $120 worth of mental energy on Tuesday as well—they are now $40 in debt. If the person repeats this pattern for 5 consecutive days, they may wake up with zero mental energy by Saturday morning and most likely remain in a state of mental exhaustion through Sunday. This fictional model tells us that we need to cultivate an awareness of how much is spent on what in our daily lives.

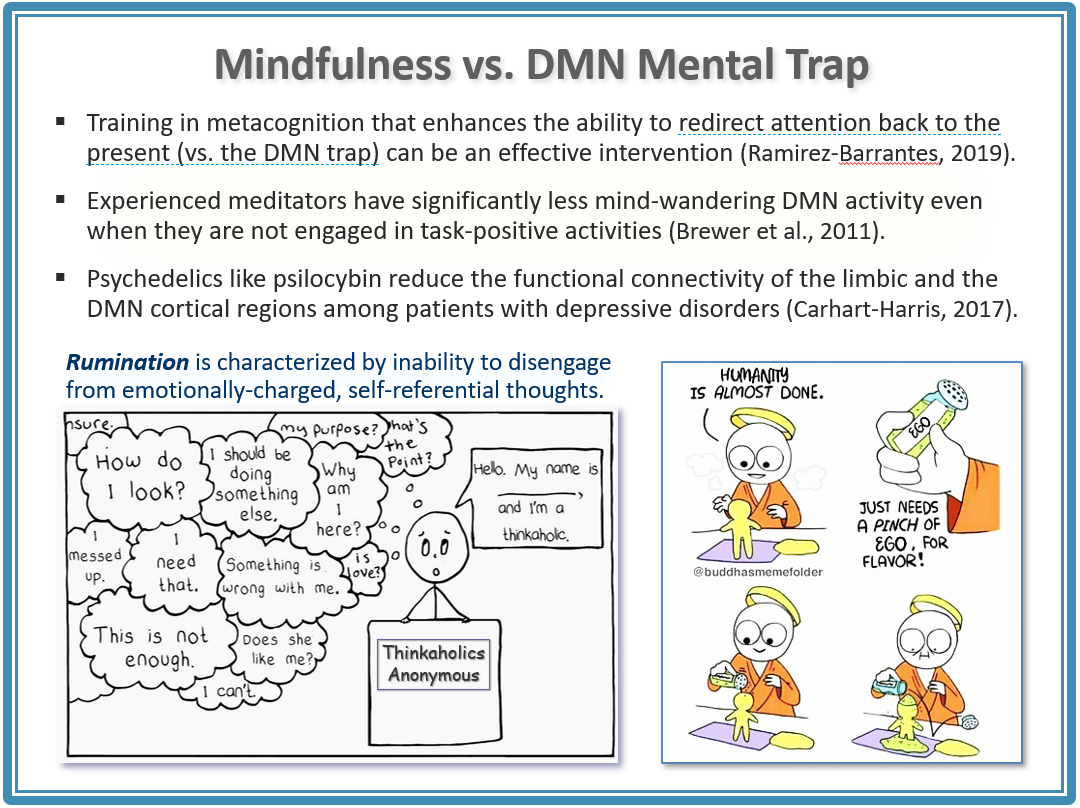

One of the most common culprits of mental exhaustion and clinical depression is not what we typically think of as hard work, but excessive task-negative ruminations (in DMN state). Here, rumination refers to unhealthy excessive brooding characterized by an inability to disengage from emotionally-charged, self-referential thoughts, which should be distinguished from goal-oriented planning, purposeful reflections, or constructive problem-solving. The draining effect of ruminations tends to be insidious because we are often unaware how significant the amount of mental energy that is being sapped by them. If we think of the mind as a vessel holding mental energy, fretting over unlikely future events or reliving unchangeable past events is the equivalent of running around helplessly with a leaky bucket. The ill effects of task-negative ruminations do not stop at mental fatigue or depressed mood. When one’s ego (seat of self-control) becomes shaky due to depleted mental energy, emotional reasoning of the limbic system tends to assert dominance over executive functions of the PFC. This partially explains why we tend to be impulsive and overindulge in comfort foods after having a stressful day. This is in addition to the commonly known weight gain associated with stress response mediated by the neuroendocrine.

We often hear about the importance of “living in the present moment,” but seemingly without logical explanations for it. Some argued that the emphasis on being fully awake to hear & now experience has been one of the most foundational, shared features of Jewish, Christian, Islamic, Hindu, Buddhist, and Taoist teachings (Armstrong, 1993; Goleman, 1988). One way to explain this age-old wisdom is the harmful effects of excessive ruminations that keep the brain in a state of aforementioned default mode network (DMN) activation. The neural circuit of DMN may seem useful in accomplishing miscellaneous tasks on an autopilot mode, but too often it keeps us lost in self-referential thoughts about lamentable past events or worries about an unknowable future. When the mind is disconnected from the actions, we stop living the fresh reality of the present moment and our lives can become dull pretty quickly and the vitality is lost. In addition to cultivating therapeutic awareness, mindfulness practice teaches us how to turn our daily activities more vibrant and authentic. It helps us to realize that everything we do in life is an opportunity to execute it with full attention, possibly one last time. By learning how to stay fully present, we discover meaningfulness in every chore instead of simply going through the motions while the mind is kept busy elsewhere. In recent decades, various studies have established a strong correlation between task-negative ruminations and mental illnesses such as depression and anxiety disorders. This is another reason why psychotherapists often remind their clients of the importance of staying connected with here & now experiences, staying out of the navel-gazing rumination traps, and staying action-oriented (behavioral activation).

We’ve learned that the navel-gazing traps of ruminations drain our mental energy and potentially lead to mental exhaustion. Furthermore, the prolonged state of DMN activation is strongly correlated with depression and anxiety disorders. Perhaps all humans living in this overstimulating, complex society are thinkaholics or at least have the potential to become one. At least it seems reasonable to assume that most of us find it quite challenging to stay connected with the unfolding fresh reality of the present moment throughout the day. Once again, the meditative practice of mindfulness when practiced correctly, provides us with the opportunity to train the attentional muscle of the ACC and reengage the frontal region of the brain with here & now.

There has been ample discussion about the historical influence of Eastern philosophies on both contemplative neuro-psychotherapy and the counter-culture movement of the 1960s (and by extension, recent psychedelia revival with micro-dosing). Interestingly, both the proponents of psychedelics and practitioners of mindfulness meditation have promulgated the need to dissolve our ego by uncovering the fundamental fallacy of self or self-referential thoughts based on their illuminating insight that the self is a mere mental construct. Given that we all have the propensity to indulge in thoughts, disconnect from the present reality, and overidentify with reified ideas, perhaps we ought to at least consider the benefit of curtailing the prevalent emphasis on and celebration of individualism often uber-amplified with the use of social media. Emerging evidence indicates that the cortical midline structures (CMS), including the mPFC and ACC regions, play a critical role in generating a model of self (Miyauchi et al., 2014). While the exact mechanisms are still being investigated, psychedelics such as psilocybin and LSD decrease the coactivation of CMS within DMN and contribute to engendering the feelings of ego dissolution (Carhart-Harris et al., 2016b; Müller et al., 2018).

All Rights Reserved ©2022 W. Okada