Dropping

During this seemingly unstimulating observation of diaphragmatic Hara-breathing and stillness of the body, the brain continues to ask what to do next and is likely to experience a strong urge to entertain itself typically by recalling past events or running simulations for unknowable future events (competing action selection regulated by the basal ganglia circuit) regardless of the level of commitment to stay connected with each breath wholeheartedly. It might be useful to know that the human brain is predisposed to continuously scan and detect the next item on the biologically primed agenda and that such survival-oriented vigilance served the species well when Homo sapiens were still trying to eke out their tenuous existence under harsh conditions. In fact, this evolutionarily primed propensity of the brain, once dubbed “anticipation machine” by Daniel Dennett, is largely responsible for stressful racing thoughts, excessive ruminations, and sleepless nights that many of us living in the complex, overstimulating modern society often experience. We also have a strong tendency to quickly lose interest in things that are not relevant to short-term goals and things we think we already know. If our attention is a hat, the brain is always looking for a new hook to hang it on. Something as seemingly unremarkable and familiar as one’s breathing, for example, usually does not sustain our attention, which makes it an excellent anchor for meditative practice. Through mindfulness meditation, we cultivate the capacity to notice one’s bubbling thoughts (metacognition), briefly acknowledge them for what they are (mental notation), and drop them matter-of-factly again and again (non-attachment) until the distracting or vexing thoughts gradually become stale and lose the power of enticement. In essence, we are altering the nature of our relationship to habitual existential agenda bit by bit, and loosening the attachment to our familiar self manifested in the bubbling thoughts while increasing the power of selective attention. Instead of getting frustrated with the inability to stay focused on the anchor, simply bring one’s attention back to the breathing Hara matter-of-factly and stay with it until the next distracting thought bubbles up.

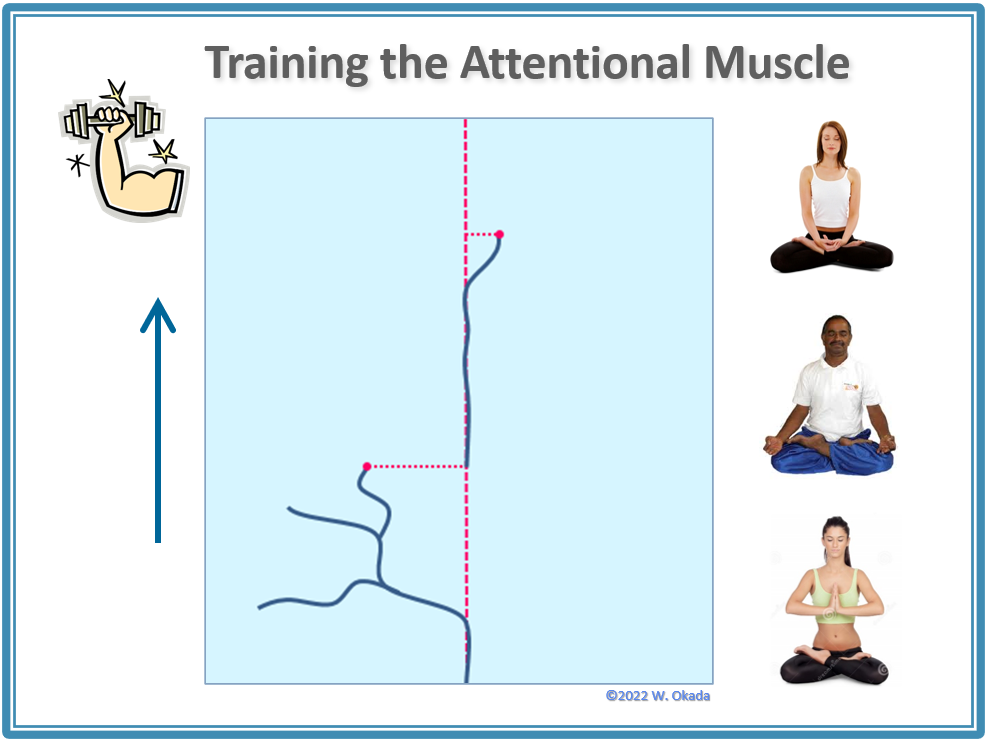

When our attention drifts away from the rise and fall of the Hara movement, we simply acknowledge the topic that distracted us, drop it calmly, and come back to the breathing Hara without getting frustrated (or without activating the limbic system). Remember that the very essence of this mental fitness program lies in this act of dropping (one’s habitual self) and bringing our attention back to the anchor represented by the dotted red line in the diagram above. Every time you drop and come back to it, you are training the neuronal muscles that support mindful awareness as if lifting weights, specifically the scaffolding network of the mPFC (medial prefrontal cortex; decision maker), DLPFC (dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; linguistic processing & working memory), and the ACC (anterior cingulate cortex; attentional regulation).

Once you start practicing regularly, you will see that diaphragmatic Hara-breathing is the most dependable ally and the source of curative power. We learn to hold the center by anchoring the mind in the observation of each breath while minimizing habitual distractions and ruminations. Furthermore, in our daily life, mindfulness practice helps us stay connected with here-and-now experiences of how things are instead of being hindered by the attachment to top-down notions of how things ought to be. By acknowledging and dropping again and again, we experientially discern and accept the inherently untrustworthy nature of our internal experience including thoughts, emotions, and bodily sensations, and see them clearly for what they are instead of chronically mis-taking them. It naturally helps us to unlearn mental and behavioral habits of unnecessarily responding to mistaken ideas that are harmful to our health.

While dropping without chasing or analyzing is the general rule of the meditative practice, sooner or later we become perceptive and attuned enough to see certain patterns and common threads in ostensibly random bubbling thoughts, such as unresolved regrets, old grudges, outdated core beliefs, catastrophizing tendency, and even agendas previously hidden from ourselves. Paradoxically, the wholehearted efforts to dismiss bubbling thoughts allow us to become acquainted with our own cognitive patterns and internal landscape and provide the therapeutic insight essential for dismantling or unlearning the habitual ways of creating pitfalls for ourselves. Furthermore, this very process leads to self-attunement (a.k.a. intrapersonal attunement) in adulthood as an empowering opportunity to make up for misattunement in earlier stages of life. More on these topics later.

All Rights Reserved ©2022 W. Okada