Breathing

In our daily lives, most of us are not paying particular attention to how each breath takes place to breathe us. It is generally understood that the involuntary, autonomic nervous system (ANS) is responsible for regulating breathing patterns (among other vital functions such as heart rate) so that we can pay attention to supposedly more pressing matters. For those of us coping with busy lifestyles, paying close attention to how one’s body is breathing may seem like a luxury; however, considering the fact that our body is unceremoniously repeating the cycle of inhalations and exhalations about 22,000 times a day to nourish many trillions of cells in the body, we may be able to appreciate that how we take each breath significantly impacts our cognitive functions, mood, and long-term health outcomes.

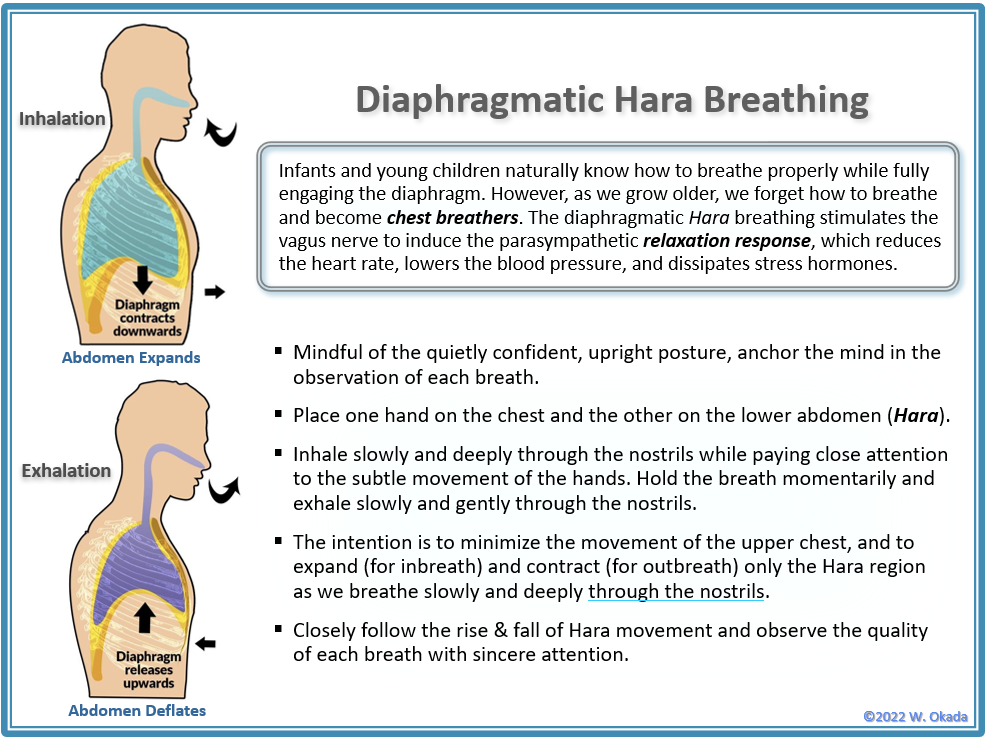

Infants and young children naturally know how to breathe properly (especially during their sleep) by fully engaging the abdominal movement actuated by the large parachute-shaped muscle called the diaphragm designed to repeat descending contraction for inhalation and ascending relaxation for exhalation underneath the lungs. However, as we grow older in this stress-ridden environment, we all seem to forget how to breathe properly and become chest breathers, whose breathing patterns are characterized by shallow breaths and tension in the shoulders and neck. Diaphragmatic breathing (a.k.a. abdominal breathing) stimulates the aforementioned vagus nerve and induces a parasympathetic relaxation response, which in turn reduces the heart rate, lowers the blood pressure, dissipates stress hormones, and supports affect regulation. In other words, many of us are in dire need of rehabilitating or re-educating the diaphragmatic inspiratory muscles in order to resume breathing properly again.

While our bodies may seem to know how to breathe and sustain countless bodily functions without any deliberate input from us, we can also consciously regulate breathing patterns as needed. For this reason, it has been said that breathing straddles the interphase between the conscious and unconscious, controllable and uncontrollable, and ultimately body and mind. For those of us trying to re-educate the diaphragm with mindful breathing, it may also be useful to know that each breath we take is unique and cannot be repeated. Since no two persons are exactly alike, each breath we take is a natural phenomenon observed only once in this universe. In addition to the Posturing guidelines on the preceding page, you might find the following tips helpful when settling into a meditative state.

Mindful of the quietly confident, upright posture that embodies one’s dignity and self-respect, anchor the mind in the observation of each breath (ref. #11 Posturing section).

Place the palm of one hand on the chest and the other on the lower abdomen (Hara) beneath the navel. Inhale slowly and deeply through the nostrils while paying close attention to the movement of the hands. Hold your breath momentarily and exhale slowly and gently through the nostrils.

The intention is not to move the upper chest and expand and contract only the Hara region as you inhale and exhale slowly and deeply through the nostrils. The Hara should expand and the navel should move outward as you inhale. Except for the Hara region, no other part of the body should move during mindfulness meditation.

Closely follow the rise and fall of the Hara movement and observe the quality of each breath with sincere attention as you anchor the mind. At this point, release the hands and place them on the lap; the palms facing up and the shoulders relaxed. Notice that no two breathes are exactly alike. When the mind drifts away, bring it back to the observation of breaths matter-of-factly.

Please refer to the website Disclaimers.

Benefits of Nasal Breathing

Keeps the diaphragm healthy & strong — Compared to mouth breathing, the relatively restricted airway through the nasal cavity encourages the diaphragm to work harder and the slower breathing pattern contributes to a larger lung capacity. Weakened inspiratory muscles are correlated with hypertension and reduced bioavailability of the vasodilator gas, nitric oxide (NO).

Increases the bioavailability of Nitric Oxide — Nasal breathing increases the bioavailability of nitric oxide (NO) secreted from the paranasal sinus, which in turn supports endothelial functions, lowers blood pressure, and improves oxygen uptake and delivery to many trillions of cells throughout the body. It is known that deficiency of nitric oxide impedes the transportation of oxygen and essential nutrients to the brain and body and causes brain fog, fatigue, and inflammation. >>> Endothelium is a thin membrane that lines the inside of the heart and blood vessels, and the endothelial cells release substances that regulate vascular relaxation and contraction as well as enzymes associated with blood clotting, platelet adhesion, and immune functions.

All Rights Reserved ©2022 W. Okada